People

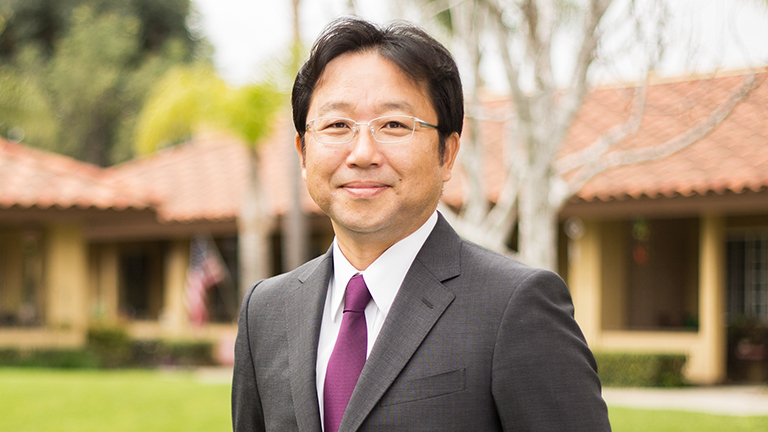

Takuma Honda

Senior Manager

Space Business Department

Mitsui Bussan Aerospace Co., Ltd.

The space industry is expanding at warp speed as the miniaturization of satellites drives down both their launch and manufacturing costs. Building on his academic background in space exploration robotics, Takuma Honda is working to create new space-based business models.

Taking over the launching of small satellites from the ISS

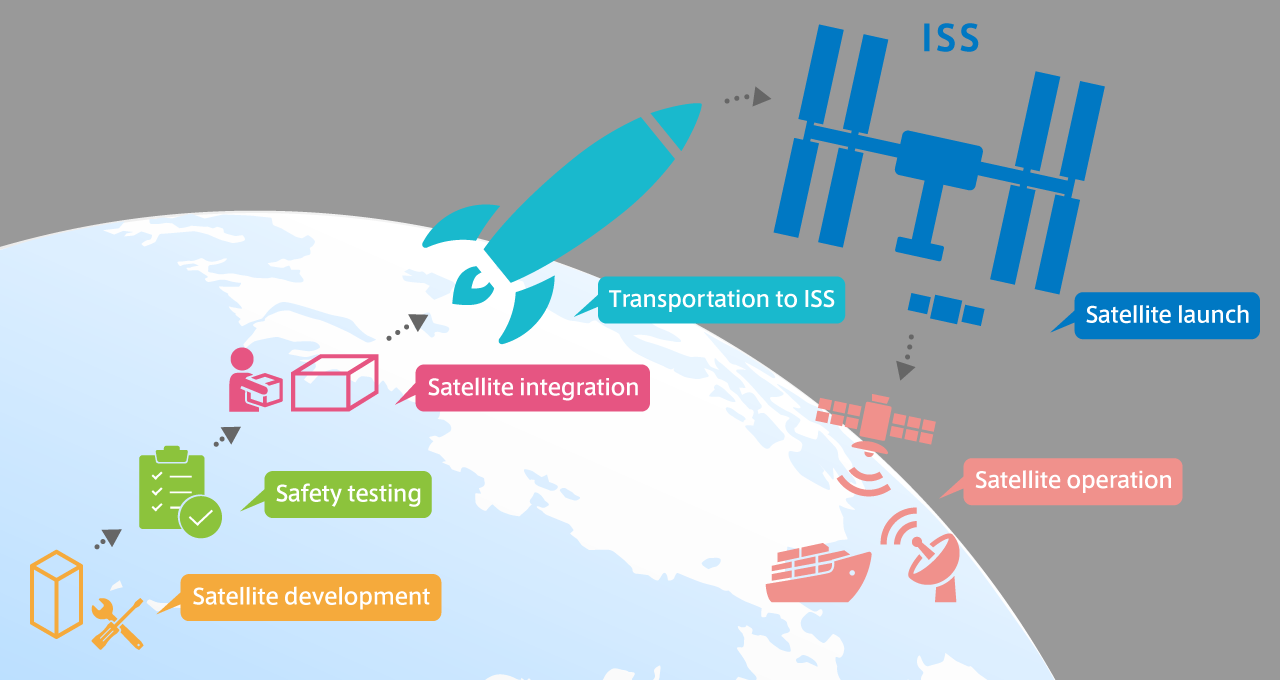

I work on the space side of Mitsui Bussan Aerospace. Specifically, our business involves launching small satellites from Kibo, the Japanese experimental module attached to the International Space Station (ISS) which orbits the earth at an altitude of 400 kilometers.

I’ve loved the idea of robots in space since I was a kid. My dad and I were already building models of the robots from space-themed cartoons when I was three! Things only got worse from there and by the time I got to university, I was studying bipedal robotics, then doing space research at grad school. My specialty wasn’t rockets, though; it was space rovers used for small asteroid exploration. I’m pretty hardcore!

I’m really lucky to have managed to turn my lifelong passion into a job. Though admittedly, space exploration robotics is not exactly what I’m working on.

Launching small satellites from the Kibo module was originally handled by JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, but in 2018, JAXA decided to outsource the service to the private sector. We put in a bid and Mitsui & Co. was selected as the service provider.

When it comes to the size of cubesats, the smallest modules are 10 x 10 x 10 centimeters. This size is referred to as “one unit,” or “1U” for short. You can put several smaller modules together to create a larger one. A 3U model, for instance, would be 10 x 10 x 30 centimeters.

Universities tend to use 1U satellites for research, while the average size for commercial companies is more like 6U. A 1U satellite is small enough to sit comfortably in the palm of your hand. Small satellites like these are opening up new opportunities in space.

What we do is send these satellites up to the ISS in low-earth orbit, then use its robot arm to launch them into space. Our principal responsibilities are customer development, safety testing and shipping the satellites to locations that JAXA requests.

Miniaturization has led to a plunge in the manufacture and launch costs for satellites. That in turn has created all sorts of new business possibilities. For example, there’s an American company that’s put a network of over 100 3U camera-equipped satellites into orbit to provide almost real-time Earth observation. A traditional large satellite could only monitor a specific location on the Earth about once every two weeks. With small satellites, because you can deploy more satellites, you get much higher frequency geospatial data. It’s revolutionary.

Naturally enough, JAXA is expecting Mitsui to add value to its overall business. Our aim is to leverage Mitsui’s globe-spanning network, marketing muscle and creativity to extend the utilization of space to a new and broader audience.

One way we plan to do that is through a one-stop service, covering satellite development, satellite launch, and satellite communication and control from ground stations. If we offer all the necessary services in a convenient bundle, we can help more businesses gain easier access to space.

That’s not all, though. Getting more people and more companies—advertising agencies, food manufacturers and toy companies are examples—to think about incorporating space into their businesses is one aspect of our job. We brainstorm ideas for how a particular sector could use space, approach them with a proposal and create demand that way. We already have several projects that are moving ahead.

Selling jeans in the Gold Rush

At the moment, there’s a rush of new players, mostly startups, piling into the space industry. Projections have the industry growing from total revenues of $366 billion in 2019 to more than $1 trillion by 2040. At the same time, the market is unknown and uncertain. All sorts of services are being created—but who knows which ones will survive long term?

That’s why we’ve devised a business model that we liken to “selling jeans in the Gold Rush.” In the Gold Rush, some entrepreneurs achieved huge success not via the risky business of prospecting for gold themselves, but by selling jeans and other kit to the prospectors. In the same way, we want to be a tool and service provider that can offer value to any business that uses cubesats.

Whatever business a company is in, launching a satellite is always the necessary first step. Launch is like a checkpoint that everyone has to pass through regardless. Steady future demand is a given.

That was the thinking behind our 2020 acquisition of the US company Spaceflight. Spaceflight is the biggest player in satellite rideshare services. Mitsui teamed up with another Japanese firm to buy 100 percent of it. It’s almost unheard-of for a Japanese company to buy an American space business outright, so there was a lot of buzz around the deal.

In the space industry, ridesharing refers to a service that allows the satellites of multiple operators to share a single rocket and fly into space. Spaceflight doesn’t handle the actual launches itself, though. It has an extensive network of launch vehicle providers that it matches against the needs of companies, non-profit organizations and government entities so they can achieve their mission goals.

I see a lot of potential synergies there. I think we can leverage this network for the business of Mitsui Aerospace.

Creating a space venture with two of my peers

My first posting at Mitsui was in the mobility domain. I worked at a car dealership business in Russia. I enjoyed the car business, but as a lifelong space enthusiast, the urge to get into a business connected to space was always gnawing away at me!

That’s why, in my second year in Mitsui, I applied to the company’s intrapreneurship system for new business creation. I made the application with two of my peers who’d joined at the same time as me. We lived in the same dorm and we used to talk a lot.

Our business plan was about providing maintenance services for orbiting satellites. Sadly, the project didn’t work out, but the experience and the connections I built back then are proving very useful to me now. Looking back, it was a valuable experience.

Under Mitsui’s intrapreneurship system, you had to keep doing your main job in parallel with developing your venture, even after you’d won official approval. My boss was amazingly supportive, though. “If you’re serious about your plan, why not devote all your time to it?” he said. I owe him a lot.

The whole thing was harder than I thought. Previously, whenever I came up with an idea, I’d been able to bounce it off my boss and senior colleagues and solicit their feedback, something which does wonders for your confidence.

It’s a different story when you’re trying to turn your own idea into a viable business and all the risk and responsibility is on your shoulders. There’s no one to point the way for you. We had to do all the thinking for ourselves, particularly as Mitsui was a company with no knowledge or experience in the space industry at that time. Making decisions based entirely on your own conviction is hard, but the experience gave me a pretty good idea of what goes into building a business from scratch.

New ways of using space in the coming years

I have two personal ambitions for the future. The first is to come up with a way for Japan to have a more significant presence in space of the post-ISS era. The second is to get more people—regular people—to see and experience space as a part of their lives.

As I said earlier, my postgrad research topic was space rovers. At the JAXA Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, I was involved, as a student, in developing a rover for one of the later versions of the Hayabusa space probe. I was blown away by the awesomeness of Japanese space technology and I developed this dream of doing great things for the world with it.

In the second half of the 2020s, it’s anticipated that government won’t be funding or managing the ISS anymore. After that, it will be the commercial sector that plays the lead role in exploiting low earth orbit. I think Japanese technology could make a significant contribution there and I hope to be part of making that happen.

But technology alone cannot drive the development of space. We need marketing-based ideas as well.

It’s very hard to envisage what the private-sector end user looks like. That’s one of the biggest challenges with the space industry. While everyone has great expectations and is investing massive amounts of money, no one’s really been able to paint a plausible picture of a way of utilizing space that justifies the colossal sums being spent on it—outside the governmental sphere, I mean.

Still, the business picture could be transformed overnight if someone found a way to link space to the happiness of the individual and give it emotional resonance. Entertainment’s a case in point. Launching a satellite to mark a special event in someone’s life is a viable idea. How memorable would that be!

How can we use space for the consumer? That’s my latest obsession. Through business, I want to help create a world where people feel a close connection to space. I mean, if you think hard enough about space, at some point you realize that, ultimately, it’s all about people. Interesting, isn’t it?

Posted in March 2021